Paying Attention: In Conversation with Heinrich and Ilze Wolff

Watershed photographed by Dave Southwood.

Jane Van Velden (JVV): Could you talk about the relationship between your research and your work as practicing architects and how these two modes inform the other. Do you see them as distinct or entangled?

Ilze Wolff (IW): I think it’s completely entangled. The research is always about gathering wisdom for what we need to do. Oftentimes it precedes the practice work, but I don’t think we can distinguish between the two. I like to think of our work as speculative research that sometimes ends up being a building and sometimes a more conceptual intervention. We work in search of a speculation or provocation. The question that we always ask when we receive a commission or an invitation to participate in the design of a building is, “What is the story here?” The story will lead you to a kind of speculation. A lot of the time there is a big story.

We’ve also found that architectural interventions in South Africa often get made without enough background wisdom and knowledge of the site. There’s a lot of research that goes into the materiality of the site—what you can see and feel—but there’s not a lot of research that goes into the immaterial qualities. We don’t really get trained to think about that kind of thing. It may at times look like two separate ways of doing, but the one is wrapped up in the other. And, of course, research needs to be funded. We don’t have an academic institution behind our practice, so our research is really run within projects on the table. The research component is part of nurturing a wider studio culture and ethic. We’re constantly teaching; Heinrich is busy with a studio at Harvard at the moment, but we don’t have a stable and continuous academic institution that finances this research.

Heinrich Wolff (HW): In many disciplines, there appears to be certainty about what constitutes research; it’s seen as though all research exists in language, or maybe diagrams. But research and knowledge can be produced in many other ways. In our part of the world, we are far clearer that language is not the only basis of knowledge. Many fields have a system of producing and legitimizing knowledge through peer-review scrutiny and restatement of ideas by quoting. This system of knowledge production does not account for speculative ideas and embodied, experiential knowledge. Why must our speculative knowledge be censored through peer-review? There is no point in curbing the imagination through that system. What is important is to advance the process of knowledge production as we generate it in practice. The need for the legitimization of research findings makes a lot of sense in medicine, for instance; if a doctor developed a new kind of heart operation, the published research claims that if you follow this method, it will have success because we’ve proven it through many successful operations. Architectural knowledge just doesn’t work like that. If we want to know about the human condition in cities, it’s a very different kind of knowledge that we require in order to act and to understand. In other words, we don’t just act in prescribed, successful ways. That is not what we are in search of. We are trying to understand the world around us, and it needs a plethora of people to understand it. We must be clear on the difference between instrumental and speculative reasoning. The nature of speculative reason is that we dare responses before action is required and that we adjust our ideas while we are enacting them. Our knowledge is circumstantial and contextual and the process of judgement is fundamental in localising our ideas. As architects we often study fragments of the world as aimless generalists. As we work, we start making links, and the beauty of those links is that they generate further speculation. That is when the wondrous excitement of design comes in—when the particularities of a project generate a network of connections between ideas.

Jimmy Bullis (JB): So this would be following up on that idea overall, but a bit more specifically for Ilze. After studying to be an architect, you studied philosophy. Do you think of that as gathering more links or nuts of knowledge and pulling from them in this way, or does it just generally foster your thinking in a more subtle manner?

IW: I studied for a degree in heritage and public culture. First, as a concern around how we look at our heritage and our built environment. In the beginning, it was situated within the architecture faculty. I was quite dissatisfied with the kind of lines of inquiry in the architecture faculty because there was a very persistent dogma around material culture, and I was not interested in that as a kind of dogma, especially when most of the material culture in our society represents a white culture. I needed other ways to think about this, which was unsupported by the architecture faculty. I moved it over to the African Studies Center, another faculty in the Humanities at the University of Cape Town. Immediately it was an experience of interdisciplinary work. My supervisor, in fact, was an archaeologist, and there were people interested in music, literature, film, the built environment, and so on. So it was very nourishing to think through and to question our discipline of architecture, because the people that I was working with were not precious about being an architect, they didn’t know what it was like to be an architect, but they cared about how their own disciplines produce a kind of a knowledge that is available for people, more broadly. I think that is the kind of methodology and thinking that we’ve developed in the practice. How do we look beyond our own architectural discipline and find ways to speak and unlearn some of the darkness we’ve learned? The histories are very violent. It doesn’t mean that we can’t engage with those histories, and a lot of the time the violence causes a kind of disengagement that doesn’t lead anybody anywhere. The interdisciplinary framework was a way of thinking through that work. It was a master’s in philosophy, based in the humanities, with a very serious look at architectural practice.

Pouya Khadem (PK): It’s not a question, but you spoke about the architectural process as being unlike a scientific process and that we should gather fragments of knowledge without a specific plan for them. I just wanted to say that this is relieving to me because I am always telling myself to be more specific and more rigid.

HW: As I said, there are different kinds of knowledge production, which are useful at different times. We sometimes feel that a “standard” method of research is used to judge the relevance of our work and by such a “standard” we are always found wanting. My brother is a professor in philosophy, and while he was studying philosophy, I attended courses with him and I was really struck by how much they read. Say you are studying Habermas, you try and read everything that he’s written, and then you read all the major critiques of Habermas, and then you put it all next to each other and you develop a perspective on what the major debates are. It’s an incredible discipline and that sort of scholarliness is valuable in certain fields, and even sometimes in architecture. But when we are trying to make a breakthrough in our work and our understandings, we have to ask ourselves what kind of knowledge production is required to inform our actions. What kind of understanding would enrich our judgment, since judgment is the way in which we measure successful interventions. Our knowledge is often produced with others and exists collectively. We need to hang out with a wide range of people, from those who know about forced removals, the appropriate size of silicone joints, and others who have a sense of urbanization, or whatever. When you work as a collective, everyone can contribute something. That is where an office is much stronger than any one of the individuals. But this focus on fragments is important. How do you gather very basic fragments, how do you amass them, and then how do you extrapolate? It’s not a random act of collecting fragments. So, with something like the forced removals of thousands of people, maybe there are only ten people that we can interview. We can have first-hand accounts of what they experienced. You don’t say you don’t want to speak to those people because it doesn’t tell the whole story. Of course, the story is bigger than those ten people, but those ten fragments give us a very focused sense of the emotional landscape that was left behind after the forced removals. A fragment is a valid form of understanding, under certain conditions.

JB: You seem to have this approach where networking knowledge, people, or various ideas is taken equally as seriously as other knowledge-making processes. This has a certain potency in the work that you’re doing, which is likewise distributed and meant to serve a lot of different people.

HW: Jane will know from philosophy, this whole thing of the justification of knowledge. Fragments justify understanding in a different way from comprehensive studies, and speculative thinking is different from instrumental thinking. I think it’s important to understand when you need the one or the other. When you want to understand the hearts and minds of people, instrumental thinking is insufficient.

JVV: I think I moved away from the field of philosophy because I felt too hesitant to insert myself. I felt like I needed to know far more, that I needed a comprehensive understanding before I could speak to an issue. I feel like architecture allows a little bit more freedom in moving and responding.

HW: We know how to play, and philosophers aren’t as playful. They know how to analyze and to compare. Sometimes that is important, but good architects should be like children at times. Playful and irrational action can be integral to a professional practice. I know very few brilliant architects that are just super systematic. You’ve got to be able to play, joke, and have fun.

JVV: I think that need for play and kind of experimentation perhaps comes in part from an expanded set of stakeholders in the architectural process. I wonder, in thinking about your research and work with the Bessie Head project, if you could speak a bit about the different people involved. From working and developing a relationship with the heritage trust to the audiences and communities that you’d help to curate at the exhibition in the biennial or in the site visits to rain clouds.

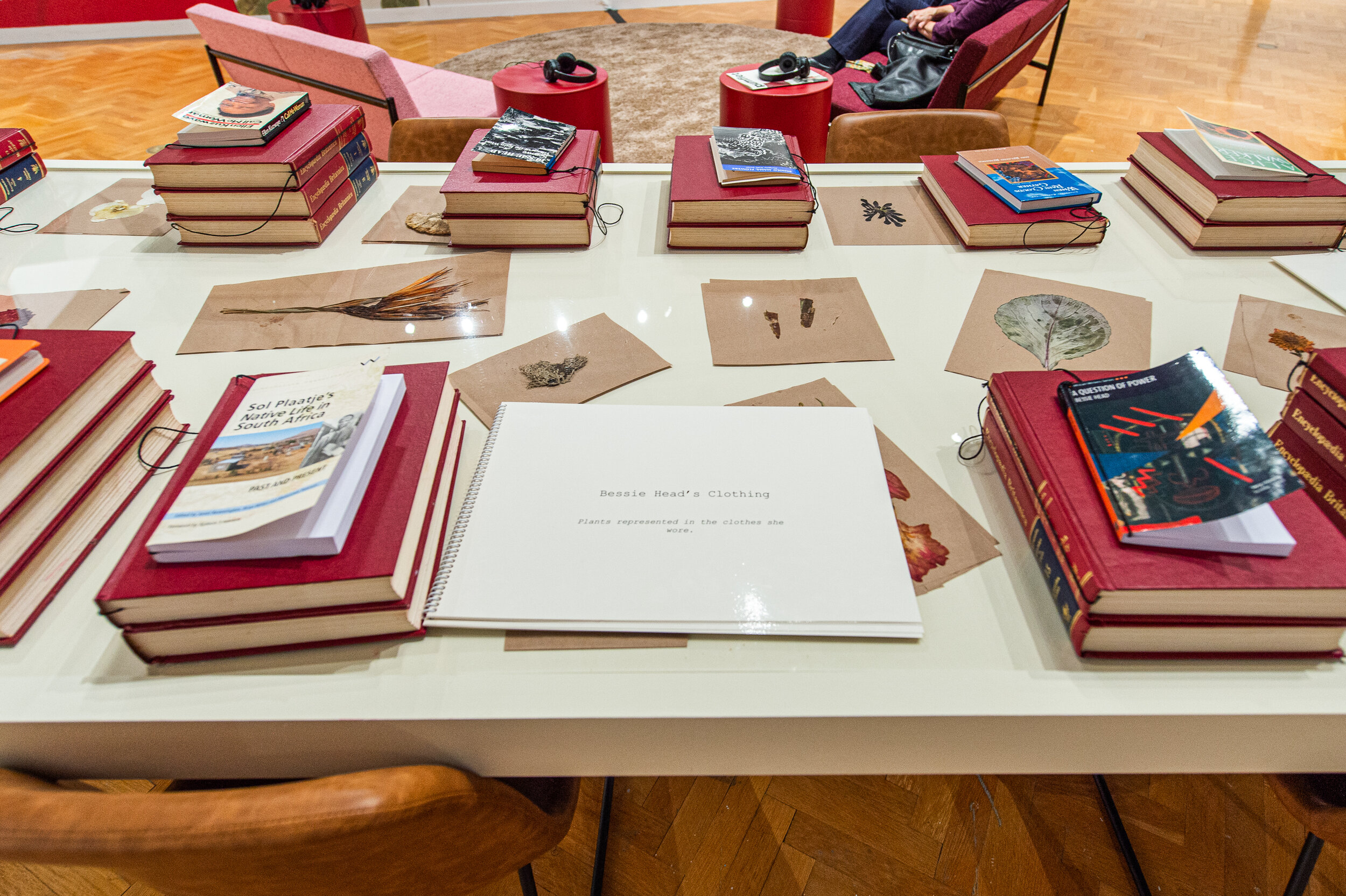

IW: We used the house as a focal point because with architecture biennials you must have something spatial. I must also give a lot of credit to the curators because they were totally open-minded individuals. Yesomi [Umolu], Sepake [Angiama], and Paulo [Tavares] asked us for our proposal nine months before and we could have very frank discussions with them about the fact it was still very unclear. You have to have an idea of what is going to be on exhibition in Chicago a year in advance, and as a team, we’re not interested in thinking of some final product upfront. We’re interested in the process. So we described our process, and that it would be episodic, with workshops, with discussions about Bessie Head. At the time it wasn’t even about Bessie Head, it was about this issue of land and how we can find protagonists in this research around the removals of people and with Sol Plaatje being a kind of a chief protagonist. In the end, it became this story of Bessie Head and her friends in Botswana, who created a communal garden at a time when South Africa was experiencing some of the most violent forced removals. I wanted to play up these two stories of creation in the shadow of destruction of people’s livelihoods.

In order to do that, the idea of collective practice becomes so important. How do we do this collectively? How do we pay homage to that practice? It is to actually begin a kind of a garden with this project. The Bessie Head Trust was completely open to that idea and helped us find links. We worked in the archive. We spoke to filmmakers. We spoke to some local scholars that had a very deep interest in her work. One example is that we realized that it would be nice to collect plant fragments from all the sites we encountered through this process and then display these plant fragments in our office. But in that moment of display, we can also make available the list of plants that we’ve also encountered through looking at the work and book covers of Bessie Head’s novels and the communal garden and then invite people to bring the actual plants to our office as part of a conversation. A lot of people came with plants that were directly linked to their knowledge of this writer and her work. It was fun. We didn’t know where it was going. There was a clear map, there was a kind of a process, and there was a lot of support from the curators. In the end, the Chicago Architectural Biennial is just one fragment, or consolidated fragments, of this process: the publication, the film documentation, the plant fragments, the mural, and the conversation space, which we wanted to open up to anybody.

JB: What do you think the role of narrative is in architectural practice? In thinking about your search for protagonists and how architects tend to populate their buildings with stories before they exist—and maybe use this as a way to explore or test something—but how does it operate in your mind?

IW: It’s crucial to the thinking around any project. I spend a lot of time reading poetry, literature, research, and stories. With the research I did on the factory, I was quite inspired by Russian literature, and one thing that astounded me is that the book would be called Anna Karenina, but Anna Karenina is one fragment of a very big story with many other characters that illuminate the story. The book tells a story of Russia at a particular time. So, one can do the same with buildings. A building tells us a much bigger story than the actual building itself. How do we then solicit voices that seemingly are in the shadows of this big building? It’s a meaningful way of understanding the story and a methodology that’s part of our practice. It’s about looking at the small stories alongside the big one which is the space, narrative, and main protagonists. I don’t think it’s narrative as a technology, but it’s a particular methodology.

HW: There is also the question about the character of the narrator. In architecture, there’s a long tradition of the omniscient narrator, the know-it-all, domineering, central reporter of everything. We don’t like that. As much as I like Peter Zumthor, his work belongs to that tradition. It’s a certain way of narrating. You go to the baths at Vals and Zumthor’s ghost is everywhere; you hear his voice. That’s one kind of a story, but there’s something about having a multitude of narrators and perspectives. Why do we not know the builders who built the Zumthor baths? Why does Zumthor dominate the story?

The way to undo that tradition is to acknowledge a multitude of voices. Then we suddenly have a sense of different actors telling their side of the story or having shaped the space. The other dimension of narration that we’re very interested in is its structure. There are many ways to tell a story, but the most exciting stories are ones with humor. Ilze and I have a certain interest in humor as a form of telling a story because there’s inevitably some surprise. So, if in the unfolding of spatial sequences or diagrams everything is just what you expect, it becomes just too factual. That’s the issue with early Modernist work, where form follows function. The problem is that the result comes entirely from a certain set of facts. That makes for very boring storytelling. It’s like putting a whole host of facts together and then hoping for a story. So the twist and the joke is very important.

JVV: In many of your projects you expand the initial brief that’s given to you or redefine it in different terms. Could you talk about that process and of creating larger constituencies that are not necessarily addressed upfront or immediately in the brief?

HW: It’s very important. Some people say we’re always trying to make projects bigger. Inevitably you need to understand the larger context to do just what you were asked to do.

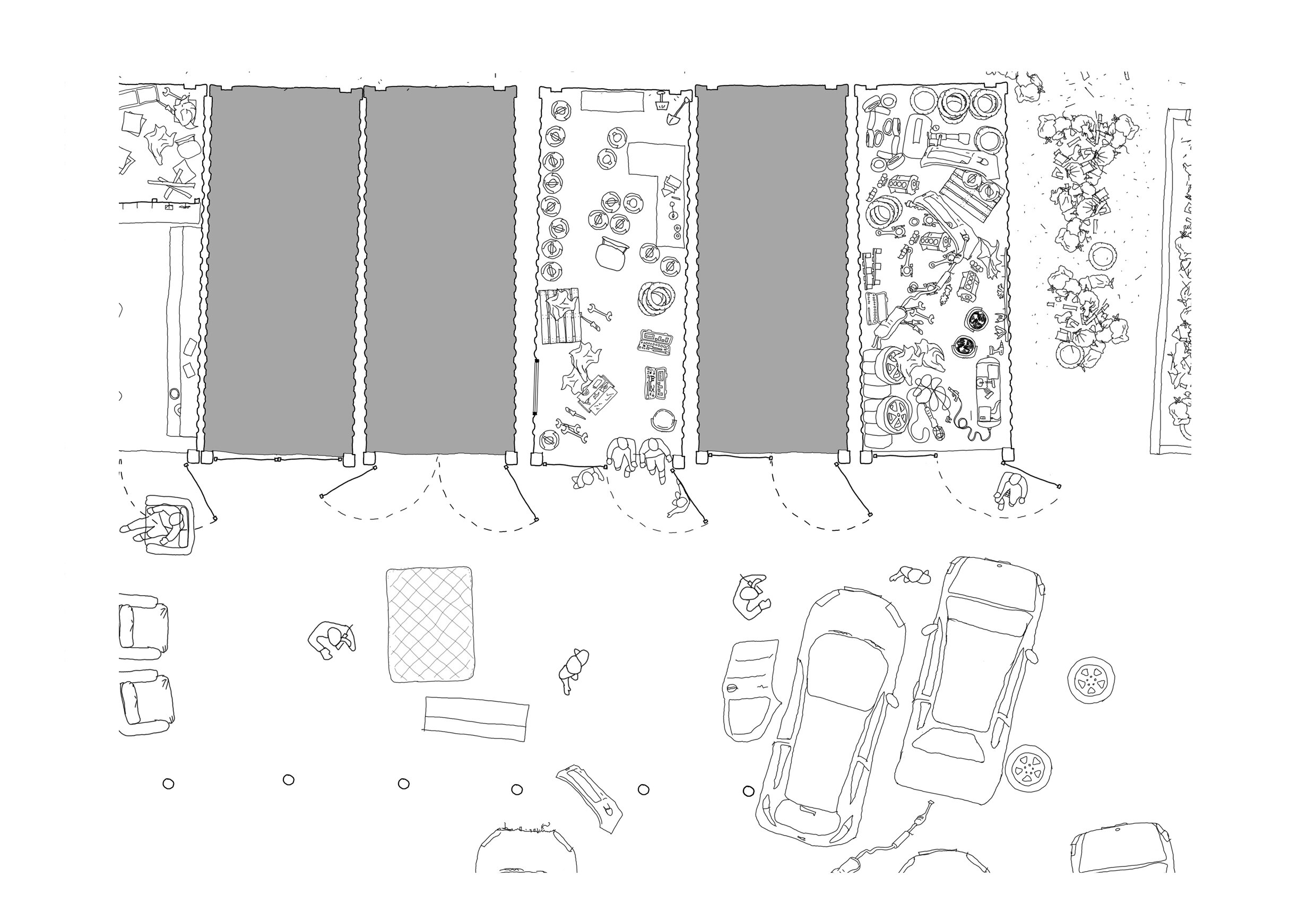

IW: I think it goes back to this point of paying attention. Somebody once came to us wanting to put a coffee shop into this shed in the biggest tourist destination in southern Africa, thinking that the coffee shop is going to create urbanity. You can’t work like that. Luckily, in that case, the clients were very interested in the commercial success of that space, so they were open to thinking beyond a coffee shop. It ended up being this project, the Watershed. A project that explores the relationship between the theory of commerce on the first floor (the business incubator) and the real-life of commerce on the ground floor (the market). This approach comes with various degrees of success.

HW: I can maybe illuminate another part of this strategy. As we said, we don’t believe in the genius author. There’s a long history in architecture that it’s great designers that make great designs. The origin of great design might instead be in strategy. We work on many standard public buildings like schools and hospitals. How do you make that a truly scintillating building like you’ve never seen? Is that by fulfilling the brief? Never. Because the brief usually has a building implied in it. Again, it comes back to the structure of the joke. It comes from outside of this narrative. And it’s in that way that you want to study the bigger context, because in the bigger context there are usually challenges to the stability of that project. So for instance, we did a school once where the brief was the same as every other school in the rest of the province. We found new legislation around vocational training. Adding this element made the project a rare school. This idea that we are doing something rare raises people’s expectations, and for us that’s a fundamental strategy of getting people engaged in the design. I don’t need them to think that we are geniuses. I need them to expect that this is going to be an exceptional project because then they will push this project and support this project. You need to inspire people into thinking that something absolutely extraordinary is about to happen. Very often it lies in the greater context. By the time you put pen to paper to make the configurations, you already have the kernel of a great project. That is because relationships and ideas are mobilized, and then you basically find the architectural corollary. You can’t have a boring brief give rise to authentic form. I just don’t think great projects unfold like that.

JVV: I think something amazing in that secondary school project that you bring up is the way that it engages the street and a larger group of users beyond those who are attending the school. You create these public platforms in a lot of your works, including the Watershed. What is the process of creating those kinds of spaces in your work?

HW: Many years ago, Ilze and I once gave a talk called The Battle for the City. There is the sense that we have increasing conglomeration and decreasing urbanity. And that is a huge societal trauma. The footprint of the city is getting bigger and the cityness of the city is actually getting smaller. There are more cars and reduced mobility, less human connection, less connection to our history, and so on. That is not a way to live as a society or as individuals. There is just no relief from that. There’s a sense that you are trying to build the public domain and create new patterns of assembly or advance pre-existing spatial practices. It’s important to create a public domain that talks to the pre-existing public domains, such as social spaces like cinemas that used to exist. There is a sense that one must either invent spaces for new needs or reinforce existing spatial practices, but we cannot do without this social domain. For instance we did a school recently for students with special learning needs where we were asked to make a corridor between classrooms, and we thought to ourselves, “Where is the public domain? How can we possibly have these kids being educated in the absence of a public domain?” How do they learn to be employed? To socialize with others? To cross the road? To do all these very basic things that are a part of the public domain. In every project we try to find ways to make the public domain more extensive rather than smaller. That’s why you see very few people ask us to do luxury houses. I think what people read implicitly in our work is that we always expand the public domain, expand the participation of others, and bring other issues into the work.

IW: I wanted to add to this idea of a public space that when we look at these histories of erasure and forced removals of major tracts of land and neighborhoods in our city, when you read the transcripts of people’s memories around what they experienced in those neighborhoods, they don’t often talk about the buildings. They talk about the public spaces. They talk about the gathering moments, the communal practices, and the sense of being together in spaces. So the cinemas stand out as spaces like that. Communal wash houses, too. We don’t have a culture of public squares in the European fashion. The street is the kind of public domain in our society, although there are many spaces in rural African villages where people come together in square-like spaces. So when we look at architectural space, we try to recuperate that within every project that we do. The public space really has to dominate, otherwise, it is not really an ethical project for us.

Heinrich Wolff is an architect and project manager with over 20 years experience. His work has received many awards including the Daimler Chrysler Award for Architecture (2007), the Lubetkin Award (2005) and in 2011 he was elected as the Designer of the Future by the Wouter Mikmak Foundation. He has held several academic appointments; he has been a visiting professor at the ETH in Zürich (2014-2015), IUAV in Venice(2013), Washington University in St. Louis (2015) and has been an adjunct associate professor at UCT, Cape Town.

Ilze Wolff is a partner of Wolff and graduated with a B.Arch at the University of Cape Town. She received a Mphil in Heritage and Public Culture, African Studies Unit, UCT. Ilze co-founded Open House Architecture in 2007, a transdisciplinary research practice which she continues to direct parallel to Wolff.

Both principals have taught and lectured internationally including Switzerland, Germany, Italy, USA, Canada, Japan and India and continue to do so. The work of the practice has also been included at various international exhibitions including, the Venice Architecture Biennale, Shenzhen Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, the Chicago Architectural Biennale, the Sao Paulo Biennale and the South American Architecture Biennale.